Congressional candidates from CT’s most unequal district weigh in on disparity

Posted: November 3, 2014 Filed under: Politics Leave a comment » The two candidates running for Congress in the Connecticut district with the widest economic disparity talked in a debate last week about what they’d do to close that gap. Democratic incumbent Jim Himes and Republican challenger Dan Debicella both agreed that the disparity is a problem, but they took different approaches to how they’d handle the issue.Himes said the disparity is clear as you travel from affluent towns like Greenwich and Darien to Bridgeport, “where an awful lot of people are living below the poverty line.”

Himes said regardless of what party people are in, “we feel that that’s not quite right.”

Here’s Himes’ full response:

Himes said the key to addressing disparity in the region is education.

“We need to fix the failing schools that unfortunately are keeping our young people in communities of need back, that are not offering them the kind of opportunity to live the American dream.”

Himes said he’s glad the country is having a good, if antagonistic, conversation about how to solve the education issue.

Himes said he supports raising the minimum wage. And he said it’s a problem that tax benefits tend to help only people at the top of the income level.

“We ought to try to restructure our tax code and the subsidies that we give as a government to actually help those people who need help and who are struggling today.”

Debicella said the disparity question was very personal to him, because he grew up in Bridgeport, with a father who was a police officer and a mother who was a secretary. He said he’s the first in family to go to college.

Here’s Debicella’s full reply:

Debicella said the American Dream is threatened for too many families.

“This is an area where we have to stop talking about income inequality and start talking about social mobility.”

Debicella is proposing what he calls enterprise zones in areas of Bridgeport, Norwalk and Stamford that are the most in need of jobs, where businesses wouldn’t be charged any federal or state taxes, and the federal government would pay local property taxes.

He also said we need to reform education.

“Specifically we should be taking the lessons of charter schools and bringing them into the public schools.”

Debicella is also proposing what he’s calling urban innovation zones in education “that allow local boards of education , teachers and parents, to determine things like curriculum for themselves, rather than having some bureaucrat or politician tell them what to do.”

He said we need to stop what he called “scare tactics” and start talking about the American dream again.

Big money donors make up most Congressional campaign funding in Conn.

Posted: October 23, 2014 Filed under: Politics Leave a comment »A Public Interest Research Group study released this week says big-money donors make up a significant majority of funding for the most recent Congressional primaries in Connecticut. Seventy-one percent of all donor money in Connecticut came from donors who gave more than a thousand dollars. That ranked Connecticut 16th in the country for its percentage of big donations. (New York came in 5th).

Evan Preston of the Connecticut Public Interest Research Group says he’s concerned about the implications of that.

“The voices of the people that are only small donors are harder and harder to be heard,” Preston said. “Because if you can run your campaign by simply raising the money from that very small group of people that can afford to give that much then you won’t need to or have any reason to reach out to small donors and ordinary Americans that can give the amount that would make them a small donor.”

The study says 106 Connecticut donors gave enough to match all donations in each state of $200 or less.

“If the people that can determine who can run for office are just a small subsection of the population, then that poses a real problem for which issues can be discussed in the campaign,” Preston said.

New Haven starts removing controversial fence between public housing and neighboring Hamden

Posted: May 13, 2014 Filed under: Housing, Income, Politics Leave a comment » New Haven began demolishing a fence on Monday that for 50 years separated a public housing complex in the city from the town of Hamden. For some, the fence had become a symbol of racial and economic division between two communities. The economic dividing line here is actually not one of the starkest in a state with one of the widest income disparities in the country. The most recent Census figures show median family income on the New Haven side was around $33,000, and it was about $70,000 on the Hamden side. But few places have anything as symbolically and literally divisive as the fence.Listen to Craig LeMoult’s story here:

City mayors describe inequality with suburbs

Posted: April 30, 2014 Filed under: Housing, Income, Politics Leave a comment »

(L to R) Former New Haven Mayor John DeStefano, Norwich Mayor Deb Hinchey, Harford Mayor Pedro Segarra

Hartford Mayor Pedro Segarra said for the most part, Connecticut is a liberal state.

“I just think that when it comes to protecting people’s wallets, we’re a lot more conservative.”

Segarra said the fiscally conservative suburban towns aren’t willing to step in to help the state’s larger cities. Former New Haven mayor John DeStefano said Connecticut’s three biggest cities have nearly three quarters of the state’s affordable housing stock.

“The choices made 100 years ago and the choices that many of the communities of CT continue to make about who they zone out, has resulted in a separating of populations and concentrations of poverty and wealth in the state.”

That poverty is also concentrated in some of Connecticut’s smaller cities, like Norwich. Norwich Mayor Deb Hinchey, said the cities all wind up fighting for a finite amount of money.

“And where I become concerned about the inequalities is where that finite group of dollars isn’t disbursed evenly throughout the state.”

Hinchey said the state needs to reform its tax laws to be more fair. DeStefano, who retired last year after 10 terms in office, laughed at that, and said he could tell she’s new to the job.

DeStefano said cities in Connecticut need to take action to reduce their own economic inequality, rather than waiting for the state to take steps. Segarra challenged DeStefano on that, suggesting Hartford has a harder time making changes to impact the economic health of the city. Here’s their exchange.

Segarra said his administration is working on building housing to attract those higher-income people to live in Hartford. In New Haven, DeStefano provided incentives for Yale University employees to live in the city. Yale is the city’s largest employer, and provides more than $15 million a year in payments to support city services.

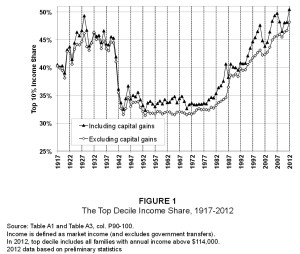

Wealthiest having much easier time bouncing back from recession

Posted: September 12, 2013 Filed under: General, Income, Politics Leave a comment »A new study by Emmanuel Saez at U.C. Berkeley says that the economic recovery has been far more generous to the wealthiest Americans than to the rest of the country. From 2009-2012, according to the study, incomes of the top 1% of Americans grew by 31.4% while the incomes of the other 99% grew just 0.4%. This chart from study shows what percentage of the total income share was held by the top 10% (decile) from 1917-2012.

Source: “Striking it Richer: The Evolution of Top Incomes in the United States” by Emmanuel Saez, UC Berkeley

As you can see, there was a serious drop-off around the time of World War II, and the levels stayed fairly constant between 30-35% until the late 1970s. They’ve now climbed back up to an all-time high.

The study was a topic of discussion today on the Diane Rehm Show on NPR. You can listen to that conversation here.

Stephanie Coontz of the Council on Contemporary Families said on the show that this is a long-term change.

“I think it’s a mistake to just think of it in terms of the recession,” she said. “It’s actually a 30 year process that has turned around all of the trends we had after the Great Depression and the move toward greater equality, and greater sense of community among the rich as well as the poor. I think the social implications of this are profound at all levels of society.”

Wall Street Journal columnist Dante Chinni, who directs the American Communities Project at American University discussed the causes of the growing disparity.

“You have the decline of good paying jobs, of manufacturing jobs,” he said. “And they were hard jobs, but they paid well. And they’ve disappeared. And that’s made life very hard. Also, automation. There are just fewer jobs available for people who don’t have a lot of education, and a lot of good skills training.”

The show’s other guest Columbia University journalism professor Thomas Edsall recently wrote a blog post for the New York Times on whether the government can actually do anything about inequality. On a somewhat related note, economist Steven Lanza looked at the issue of what difference government policies can make on the economy in Connecticut. His answer: not much. A WSHU story on his paper is here.

Also today, NPR Morning Edition’s Steve Inskeep spoke with Tyler Cowan, author of the book “Average Is Over: Powering America Beyond the Age of the Great Stagnation.” Cowan predicts the future means more people rising up to much greater wealth, as well as more clustering in a kind of “lower-middle class existence.”

“It will be a very strange world, I think,” he said. “We will be returning to historical levels of inequality. We’ll view post-war America as a kind of strange interlude not to be repeated. It won’t be the dreams that we all had that virtually all incomes go up in lockstep at three percent a year. It hurts to give that up. It will mean some very real increases in economic fragility for a lot of people.”

You can listen to Cowan’s conversation with Inskeep here.

What do you think? Let us know in the comments, email disparity@wshu.org or tweet us at @CTdisparity.

Conn. legislature considering minimum wage, retirement plan for low-income workers

Posted: May 8, 2013 Filed under: Education, General, Income, Politics Leave a comment »Connecticut’s legislative appropriations subcommittee approved two bills Tuesday related to economic disparity issues – one that would raise the minimum wage, and another that takes steps toward creating a state retirement plan for low income workers.

Hear about both bills here:

dk_bills_130508

The first bill would raise the minimum wage from $8.25 to $9 an hour over the next year and possibly to $9.75 the following year. Democratic State Representative Beth Bye of West Hartford says in the past she voted against raising the minimum wage. But now she says workers need it more than ever:

“What we’re seeing is this widening income disparity, in our state and in our country,” said Bye. “For people who are working full time I think we need to offer this as a way to help them to buy food and afford housing”

State Representative Mitch Bolinsky, a Newtown Republican, says the bill would prevent companies from hiring new employees, particularly teenagers. “The unemployment rate for that class of individual is three times higher than the state rate I see this as a job killing bill and a reason to have more kids on the street with nothing to do this summer,” said Bolinsky.

The bill is different from what Governor Dannel Malloy has proposed, which is to raise the minimum wage by 75 cents over the next two years. The committee bill still needs to be taken up by the House and Senate.

Also, the Appropriations Committee approved a bill that would require an initial feasibility study of a state administered retirement plan for low income workers. It made it through the committee on a mainly party line vote on Tuesday. Representative Jason Perillo of Shelton was one of a number of Republican members of the committee who voted against the bill. Perillo says there are plenty of private firms available to administer retirement plans for low income workers. The bill requires the Connecticut Retirement Security Trust Fund Board to set-up a low income workers fund, if the market feasibility study finds that such a fund would be self-sustaining. The bill heads to the Senate for further action.

Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz: Inequality is holding back the recovery (Paul Krugman disagrees)

Posted: January 22, 2013 Filed under: Education, Employment, General, Income, Politics Leave a comment »The New York Times launched a new blog this week called The Great Divide, looking at inequality in the U.S. The blog is moderated by Joseph E. Stiglitz, a Nobel laureate in economics, a Columbia professor and a former chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers and chief economist for the World Bank. Stiglitz wrote the initial post in the blog, entitled “Inequality is holding back the recovery.”

“Politicians typically talk about rising inequality and the sluggish recovery as separate phenomena, when they are in fact intertwined,” Stiglitz writes. “Inequality stifles, restrains and holds back our growth.”

Stiglitz argues there are four major reasons inequality is squelching the recovery:

– The middle class is too weak to support the consumer spending necessary to drive growth

– The middle class is unable to invest in the future through education or starting/growing businesses

– The weak middle class holds back tax receipts needed for infrastructure, education, health, etc.

– Inequality leads to boom-and-bust cycles that make the economy more volatile and vulnerable

Stiglitz blames the economic policies of both the Obama and Bush administrations for making things worse.

“Instead of pouring money into the banks, we could have tried rebuilding the economy from the bottom up. We could have enabled homeowners who were ‘underwater’ — those who owe more money on their homes than the homes are worth — to get a fresh start, by writing down principal, in exchange for giving banks a share of the gains if and when home prices recovered. We could have recognized that when young people are jobless, their skills atrophy. We could have made sure that every young person was either in school, in a training program or on a job. Instead, we let youth unemployment rise to twice the national average. The children of the rich can stay in college or attend graduate school, without accumulating enormous debt, or take unpaid internships to beef up their résumés. Not so for those in the middle and bottom. We are sowing the seeds of ever more inequality in the coming years.”

He offers suggestions for President Obama’s second term.

“What’s needed is a comprehensive response that should include, at least, significant investments in education, a more progressive tax system and a tax on financial speculation.”

A lot to talk about here. Do you agree with Stiglitz’s arguments? Do you think inequality is holding us back from an economic recovery? What about his prescription for fixing it? Would education investment or a more progressive tax system make a difference?

Economist and New York Times columnist Paul Krugman (also a Nobel laureate) disagrees with him. In two responses to Stiglitz (Jan. 20 & Jan. 21), he says he’d love to blame slow growth on inequality. “But I couldn’t and can’t convince myself that the theory and evidence really support that view,” he writes in the second piece. “Inequality is a huge problem – but not for employment growth in 2013 or 2014.”

One thing the rich and poor in Conn. have in common

Posted: August 28, 2012 Filed under: Politics Leave a comment »Usually on this blog we talk about all the differences between the very rich and very poor in Connecticut. Well, here’s something they have in common – they like Governor Dannel Malloy. Mark Pazniokas of CT Mirror noticed in the latest Quinnipiac University poll that the rich and poor like Malloy better than the people in the middle. He writes, “Voters in households earning less than $30,000 annually approve, 47 percent to 37 percent. He is favored 48 percent to 43 percent by voters with household incomes above $100,000.” He also points out that regardless of income, everybody disapproves of the General Assembly.

Recent Comments